Taking on a full-time apprentice is expensive, time-consuming and completely worth it. But there are lots of other ways that home woodworkers can pass on their knowledge and help the next generation of young woodworkers.

For example: Before there was Kale, there was Ty Black.

Ty was a local coder who had lost his job and then became a stay-at-home dad for his two kids (I think he got a promotion). Ty wanted to become a better woodworker and was willing to trade: my instruction for his scut-work.

Every week he (and sometimes his kids) would spend about 10 hours in the shop with me. Half the time was me showing him anything from dovetails to using wood-threading tools. The other half of the time, Ty cleaned up the shop, processed stock, improved the organization of the shop or helped with computer programming.

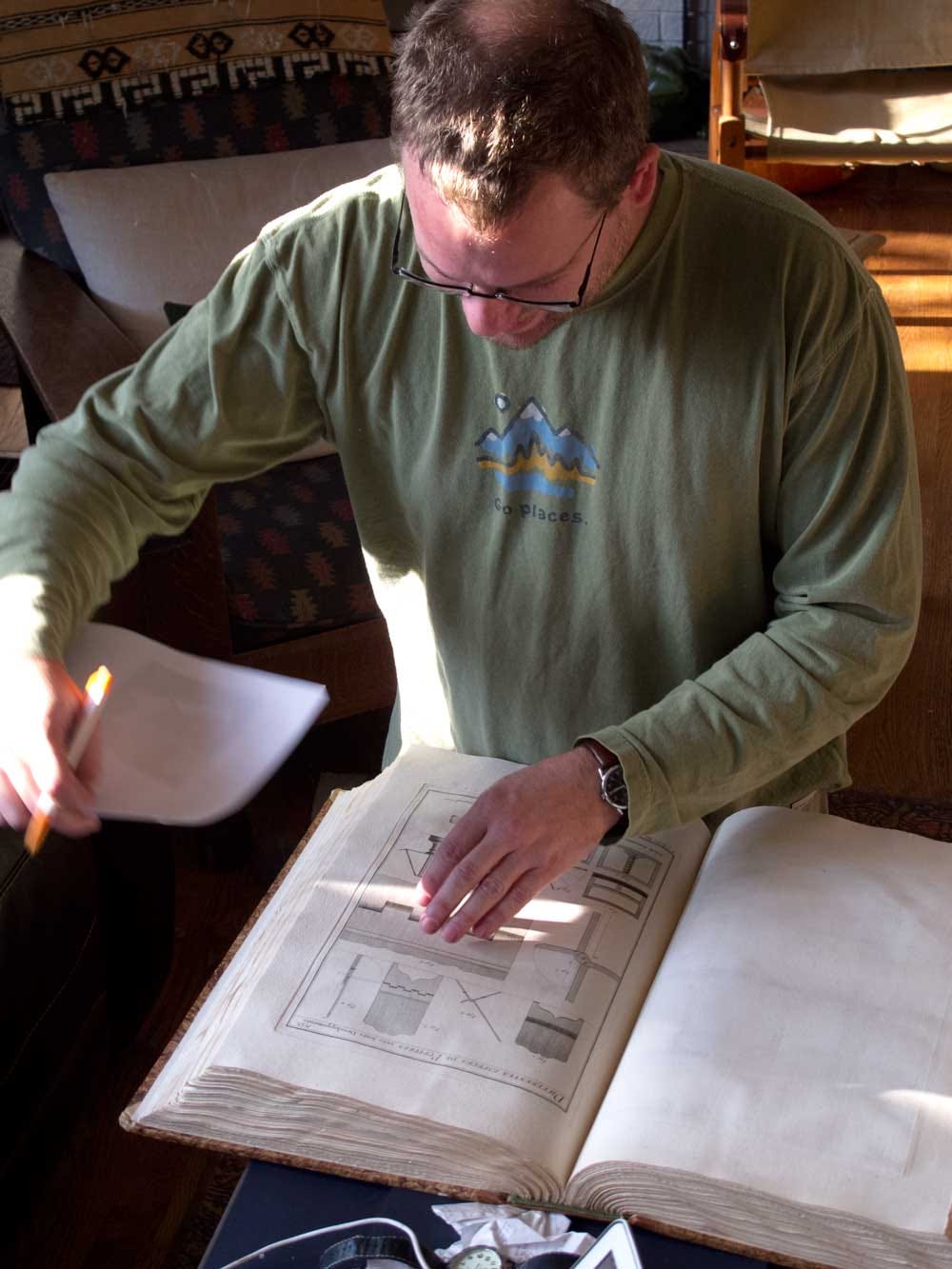

Ty developed the computer program that cleaned up all the scans and did all the OCR for our massive Charles H. Hayward project. Because of his brains, it saved us at least two years of manually cleaning images to create “The Woodworker” series.

In fact, I still refer to the spreadsheets that Ty created for us that guided us as we whittled down the articles into the four books in the series.

What happened to Ty? His wife was a resident at Children’s Hospital, so when that finished up, they moved to Florida.

He’s come back a couple times, and he’s always happy to get his hands dirty and help in the shop (or with finishing our holdfasts while wearing multiple garbage bags and a respirator….)

We all miss you, Ty.

The other baby apprenticeship program I ran was with our kids, particularly Katherine.

When I worked as a youth with my father, it was forced labor. Nearly every weekend, we drove to our farm in Hackett, Arkansas, and he put me to work as his assistant in framing and sheathing our houses there.

I was salty about it. Not because of the work. I have always loved building things. But because I had no choice, and I wasn’t being paid. Basically, I had to take off time from my work at the yogurt store ($3.15 an hour) to work for him for free. And get bit by mosquitos and chiggers.

I learned a lot about carpentry back then, of course, but I didn’t want to conscript my children into my woodworking business.

So, I paid them.

When I started making furniture for customers, I’d hire Katherine to help with aspects of the project, particularly the “make pretty” and final touch-ups.

When I was finishing a huge plywood built-in that was dyed black, I hired Katherine to touch up all the small areas that weren’t perfectly black. I showed her how to wick ink from a Sharpie into the flaw then cover it with a little wax.

And I told her something that holds true today: “This is how we’ve been hiding mistakes from rich people for centuries.”

And I paid her hourly. In cash.

After that, she was always eager to work for me. And both she and her sister, Madeline, worked for me until they left for college.

Madeline still says: “That was the best money I ever made, when you consider the work I did.”

All this is to say that you don’t have to sign apprenticeship papers in blood to do your part. I know lots of woodworkers who train neighborhood kids with great results. You just have to put yourself out there and sacrifice some of the peace and quiet in your shop.

It’s worth it.

When I was in high school, I had no idea that you could become an independent furniture maker and make a living. I thought all furniture was made in factories. (In truth, I probably didn’t think much about how furniture was made). And this was in a family where we built our own damn houses on our farm without electricity or water.

You have to be explicit with kids. You have to say: If you love this, it is possible to make a living at it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Anarchist's Apprentice to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.